Opera’s high flying star

Opera singer Michael Fabiano has been obsessed with aviation ever since he was a child.

He recalls when he was just 5 years old, his parents bought him a subscription to Aviation Week magazine. He continued reading everything he could about aviation as he was growing up and was firmly convinced he would have a career in aviation.

That is, until he got to college.

That’s when a voice teacher asked him a question that changed his life: “Do you realize the talent you have?”

Michael said no. He’d always loved to sing, but never thought of it as a career.

But his voice teacher convinced him, saying, “You have a different talent than the average student. And when you have a talent this big, you have a responsibility to the talent.”

“And so day by day, I just realized I had a deep love for singing. And I switched.”

It was the right decision.

When he was just 22 years old, he won a Metropolitan Opera competition in New York.

“Then my career just kicked into gear,” he recalls.

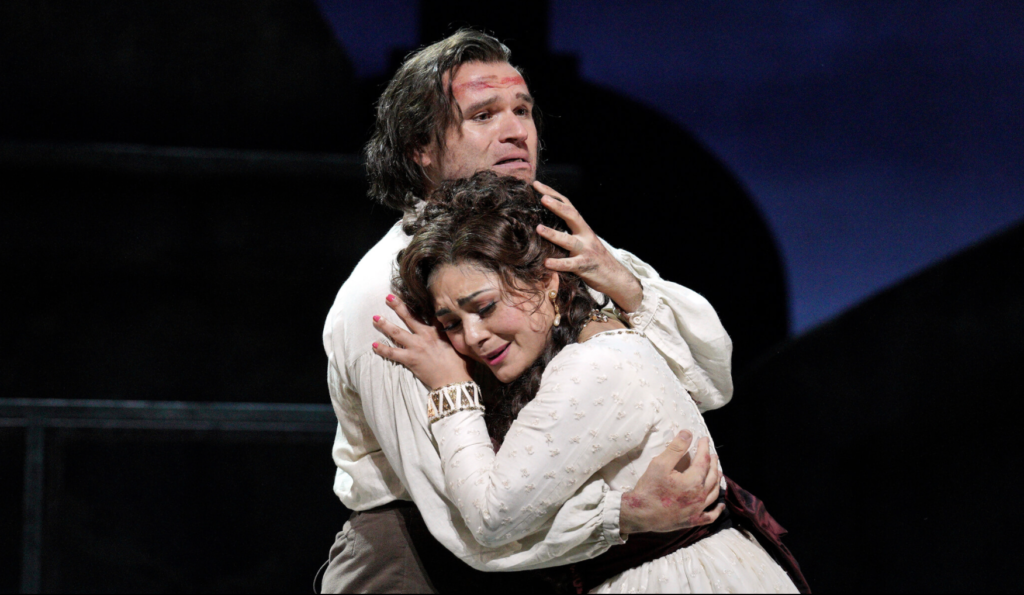

Now 36, the tenor has performed all over the world, traveling 10 to 11 months a year for his art. Just this month, he opened as Cavaradossi in the Puccini opera Tosca in Paris.

But even as singing became his career, he never forgot his love of flight.

About eight years ago, he finally began taking flight lessons while he was performing in England.

“I did all the way up through my first solo in England,” noting his first solo was in a Piper Archer and “not one with a glass cockpit,” he recalls with a chuckle.

Upon his return to the United States, he continued his flight training, eventually earning his private pilot certificate in 2016. And in March 2021 he added his instrument rating.

“Finally,” he says. “It took me forever because the problem with my career is I’m in a different city every month, more or less.”

But that changed in 2020 with the COVID-19 pandemic.

While many pilots flew much less, Michael seized the opportunity to earn his instrument rating.

And he’s not done. Now with about 500 hours, he hopes to one day earn his multi-engine and commercial tickets.

“I’d like to be able to fly a Diamond DA62, DA50, or DA42 and some other larger turbo planes,” he says. “One dream plane for me — maybe down the line — is a Piper M500 or an M350.”

Based in New Jersey when he’s home, Michael doesn’t own a plane now. Instead he has joined a number of flying clubs around the world so he can fly in the city where he’s performing.

“I fly as often as I can to stay current,” he says, noting he’s flown a variety of aircraft, including Cessna 172s and 182s, Piper Archers, Warriors, and Arrows, and Cirrus SR20s and SR22s.

One of his favorites is the SR22.

“It’s a great plane,” he says. “Not only is it a rocket ship, it’s just a joy to fly.”

While he flies as often as he can to keep his skills sharp, he also will use general aviation to travel to different performances.

“There have been many instances where I was working on the West Coast, for instance, between San Francisco and Los Angeles, or in the East between New York and DC, when I’ll rent an Archer or Arrow and transit between the two cities, because frankly, it’s a lot healthier for me to not be around a ton of people before I sing. One thing that people don’t realize is that if I get even marginally sick, it’s very difficult to perform. I’ve got to have my health. So I often fly myself when I don’t have huge distances to go. I would rather rent a plane.”

Of course, if it’s a much longer flight — like the one for his most recent performance in Paris — he flies commercial.

The Parallels Between Flying and Singing

There are many similarities between flying and singing, Michael has discovered.

“When I learned how to fly, one thing that became really clear to me is that you’ve got to be one with the plane,” he says. “Your head’s got to be clear. You cannot be focused on anything else but flying the plane. Of course, it goes in line with that moniker IMSAFE, right?”

IMSAFE is the checklist pilots use to assess their fitness to fly. It stands for Illness, Medication, Stress, Alcohol, Fatigue, and Emotion.

“IMSAFE is really important to singing too, because if I am inebriated or if I’m emotional or if I’m any one of those letters in that acronym when I’m performing, I’m not going to do my job,” he explains. “I realized that just like I have to fly the plane and do nothing else, I have to sing and do nothing else. And sometimes when you’re on stage, it’s easy to get sidetracked. It’s easy to let external issues with family, friends, love, money, and business get in the way of doing the job. And when that happens, the voice does not work.”

He takes the analogy one step further: “I’m always reminded to just do almost nothing. You know, the plane flies itself. If I just use two fingers on the yoke, that’s enough. I don’t really need much more than that. And the same goes for the voice. It requires very little input, in reality. It doesn’t require force or effort if it’s done efficiently. And if I try to do too much, it actually is not enough, which is crazy, right?”

“It’s the same for flying,” he continues. “Pulling the yoke back too hard or over manipulating the controls probably will lead the plane into distress. And so if I over manipulate my voice, I actually will be in distress. It was interesting when I was learning how to fly how many parallels there were and how much more it informed my own career.”

Another parallel between flying and singing is the constant need to keep current.

“I have to keep studying all the time, otherwise my skill atrophies fast,” he notes. “It’s just like going to the gym and lifting weights. If you stop lifting weights for three months, the small tears in the muscles start to disappear and you lose muscle mass. And the vocal cords are a small muscle.”

“The same applies to flying,” he continues. “If you stop flying even for a few weeks, your feeling of the plane diminishes fast. The skill of flying disappears very fast. I don’t have as much time under the belt as a lot of pilots, but I venture to say that if I go more than a month without flying a plane, it takes me a good hour to two hours, and a bunch of landings, to just get back in with feeling super comfortable with the plane.”